It was August 1945, and my first experience of a military hospital, which was most illuminating. Everything had to be in “apple pie” order all the time, and we had to do our best to lie or sit to attention when visited by a doctor or nursing sister. I slowly recovered and was practically better when the war took a most dramatic turn. Atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, and their surrender quickly followed. This meant the end of hostilities. Portsmouth – being a naval town and having many men in the Far East – went wild. On V.J. (Victory over Japan) night I was considered fit enough to accompany a Naval Ambulance as stretcher bearer. We spent the night picking up drunken sailors, soldiers and airmen who had been injured in the celebrations. I had never seen so much broken furniture or glass.

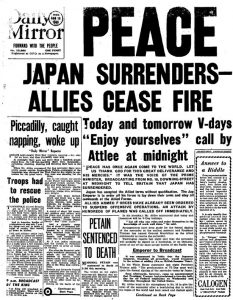

Nobody in Portsmouth on VJ Night seems to have taken any photos that I can find so this rather tame one of celebrations in The Strand in London will have to do. I notice that Marshall Pétain was sentenced to death at the same time. He was reprieved and died in a secure hospital in 1951.

On discharge from the hospital I went to Tunbridge Wells as instructed and found myself once again on fatigues and guard duty. A system of discharge from the Forces were now in operation. Everybody was placed in a group numbered from 1 to 50, and as your group number came up so you were released. My group was 25. Even though there was a shortage of teachers the Army seemed reluctant to let me go, but eventually my turn came and as it was the custom to send you as near as possible to where you had enlisted I was directed to Guisborough in North Yorkshire.

The waiting days passed very slowly, and I was given the job of writing testimonials for those about to be discharged. As I knew nothing about them, and never even saw most of them, I had to use their Army records, which were made available to me. To my pleasure I was able to write my own testimonial. I gave myself a glowing report, though the fact that I had started and finished as a Signalman was impossible to hide.

Then came the great day. We were given a railway warrant, a few days’ pay and a draft for our severance pay – mine was about eighty pounds – and put on a train for Manchester. We had also been given a paper which entitled us to claim a civilian suit, hat and coat at a depot in Accrington. After first going home, I made my way to the depot and claimed my clothing. There was one thing about it – it was hard-wearing, and I still had the coat many years later.

After a few weeks at home I went back to Middlesbrough to reclaim my job as a teacher. I was told politely but firmly that I could not go back to my old school as there was no vacancy, but I could have a job at one of the very rough down-town schools near the railway station. I accepted this reluctantly, but I could not settle back to teaching. I had a class of fifty 13-year old boys, and though I was an expert at survival this was not the life for me. After one of my women colleagues had remarked in the staff room that, “You ex-service men don’t know what it was like to really suffer in the war”, I decided to leave. I would come back later, but not to this school.

I applied for, and was accepted by Carnegie College of Physical Education for further training. Although I had the necessary qualifications I could not train as a doctor as I was already a qualified teacher. I was not really fit to undertake a strenuous course in physical education, but I was determined to try to get a qualification which would open doors other than those into the classrooms of elementary schools.