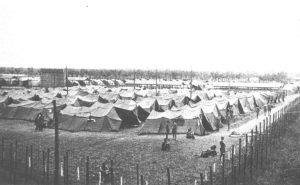

We once more entrained – this time in coaches with blacked-out windows, so the journey north remained a mystery as far as locations were concerned. After many hours we arrived at a small halt which we learned later was about twenty miles from Modena in the Po valley. We marched to our new camp to find, to our dismay, that it was still being built (shades of the modern tourism ), and we would have to live in tents until all was ready. This was not a hardship in the summer, and to our delight we were taken on what became known as ‘melon marches’. We walked to local melon plantations and were allowed to take one melon each – free of charge. These helped to assuage the ever-present pangs of hunger for a short period, and it was also a pleasure to get out from behind the barbed wire.

This is a tented POW camp near Modena. It may be the same one Dad was in.

One Bombardier of the Royal Artillery had managed to keep a copy of “Gone with the Wind” and enterprisingly he loaned it out at a cost of three cigarettes a day. Such was the demand that soon a long waiting list was formed, but the book began to deteriorate after passing through so many pairs of hands, and the pages were eventually used as cigarette papers.

We did not have to work whilst in Italy, and even with the diversion of instructional classes, story-telling, card schools and a concert-party, time hung very heavily on our hands. The meagre rations of one bowl of spaghetti and eight ounces of bread per day caused us to lose weight quite rapidly, and only the occasional Red Cross parcel kept us reasonably healthy. It was common to have a ‘black-out’ when rising to one’s feet after a period lying down, and we noted the fatness of our cooks – prisoners like ourselves -with envy. There was no structure of rank in the camp, although there was a Regimental Sergeant Major nominally in charge and consequently it became ‘every man for himself’.

Eventually the huts were constructed and we moved in. Each hut had accommodation for two hundred men sleeping in bunks in two tiers. A washroom with toilets and showers was attached to each pair of huts but the water supply was uncertain. The days passed slowly – we were paraded and counted twice per day but otherwise left to our own devices.

One day there was a special parade and we were ordered to form up according to our religion – Catholics on the right, non-Catholics on the left. We were then addressed by a Cardinal who was making the rounds of P.0.W. camps. He finished his speech in broken English with the words, ‘The Holy Father sends his blessing to his Catholic sons and his good wishes to the others.’ The Holy Father’s Catholic sons were then taken to the local Church, where there was a distribution of bread, and even wine. On realising the advantages,most of us would have converted overnight but the information on identity discs was unchangeable and C. of E. I had to remain.

There were many attempts to make the days pass more swiftly. Men with interesting past lives to reveal went from hut to hut as story-tellers, and for a few cigarettes would talk of their experiences as miners, dockers, costermongers, teachers, professional soldiers etc. Some groups spent many hours per day playing bridge with home made cards, whilst others just meandered slowly inside the perimeter wire trying to make sure they got some exercise. British army padres came and conducted services and tried to raise morale. A concert party was formed and gave a performance each week. There was no attempt to escape, chiefly because there was nowhere to escape to, and in spite of our occasional Red Cross parcels we were really not fit enough to hazard our lives. The currency of the camp was cigarettes, and although I had been a non-smoker until now, I began the practice in order to combat my constant hunger.

Many months passed. Our knowledge of the progress of the war was minimal but there was a secret radio in the camp and occasionally a sergeant who had been a reporter in civilian life came to each hut to give us the latest news. When one day he came to tell us of the Allied invasion of Italy and the landings at Salerno we were overjoyed. We thought that we only had to stay put for a week or two longer and we would be free. The Germans had different ideas.

One morning we awoke to find Germans tanks and infantry surrounding the camp. They had disarmed the Italian sentries and camp staff and they pushed these bewildered and frightened men inside the wire with us. The Italians thought their end had come, but we ignored them, for our minds were now concentrated on escape. Holes were dug in the ground and carefully concealed, and spaces were made in the false roofs of the huts. The Germans – an S.S. company- were equal to all this, and the firing of machine guns into the roofs of the huts and the movement of tanks over the whole of the camp-ground quickly convinced us that this was not the time or place to try to escape. Things had become quite desperate – the water was still on, but there was no food. Most of us had a small emergency stock from our Red Gross parcels, and on this we now had to survive. After a few days we were rounded up by the Germans and marched to the station halt under heavy escort. There were no compartmented trains this time. We were put into cattle trucks – as many as sixty men in each – and the doors were slammed and bolted. There were no sanitary facilities, and the conditions deteriorated rapidly. There was straw on the floor of each truck, but the only ventilation was from the small grill-like windows through which a man could just get his head. We set off towards Modena, and to our relief were ordered out after about six hours.

|

|

|

|