In late October I had my call-up papers forwarded to me. I was to report for a medical examination in a church hall in Middlesbrough, and to have a military interview. Both proceedings were a farce. I had made up my mind to join the Navy, but the military interviewer – a retired Colonel who seemed very deaf and whose expression was one of contempt for those being interviewed – simply told me that I would be drafted in to the Royal Corps of Signals as a driver/operator. As I couldn’t drive and knew nothing about wireless telegraphy I was not particularly enthusiastic about this decision. Soon afterwards, I received a letter enclosing a day’s pay (2/-)* and a railway warrant asking me to report to Fenham Barracks in Newcastle upon Tyne. This I duly did, and stood in a queue of young men who had been similarly bidden. We waited for many hours. It was cold – early December – and when it was growing dark we were admitted to the barracks. Lists of names were read out and mine was in one of the last and shortest – only four of us. An ageing Corporal told us we would be going later that night to Oxfordshire to join the 50th Divisional Signals. As we walked to the railway station through the blacked-out streets, carrying our suitcases, I asked the Corporal if it was possible that we could get some food. He said that we would be fed when the train stopped at York. It did not stop, of course, and to this day I have a profound dislike of York station.

We arrived at some remote halt many hours later and set off in the dawn light to walk the five miles to the Divisional location. By this time we were not only exhausted but ravenously hungry. Fortunately, on arrival at the camp site, we were given breakfast, left to wash and shave and report to the Commanding Officer at 9 a.m. He looked at us with some disdain, and as I was at the end of the line he addressed me first. The conversation remains in my memory to this day. “What were you in civilian life?” he said. “A school- master” I replied. “Good God,” he said, “have we got down to this already? Anyway,” he continued, “can you read and write?” Flabbergasted, I mumbled “Yes Sir.” The other three went through a similar interrogation. There was another teacher, a Clerk to the County Court, and an electrician. We were soon made to realise that we now counted for nothing and we had entered a world where rational thought and behaviour did not exist. The final words of the Commanding Officer were, “By the way, we’re going to France next week, so any training you require will have to be done there – you’d better ask the quartermaster if he can fit you up with uniforms, and you’d better have three days’ embarkation leave.” The last remark was more to our liking. The quartermaster couldn’t fit us up with uniforms, but within two hours we were back on the train heading north to our respective homes for leave. On walking into my parents’ home in Manchester my father looked at me quizzically and said, “Can’t you find your unit?” “I’m on leave,” I replied. “My God,” he said, “we’ve no chance this time.”

On rejoining our unit a few days later we were obviously ‘in the way’, as everyone was busy preparing for the move to France. However, we were employed as casual labourers and cleaners. No attempt was made to give us any training except for a short period of foot-drill. We were unable to salute, as we had no uniform, so we were at least spared this never-ending rigmarole, as officers rushed about the area on seemingly useless errands.

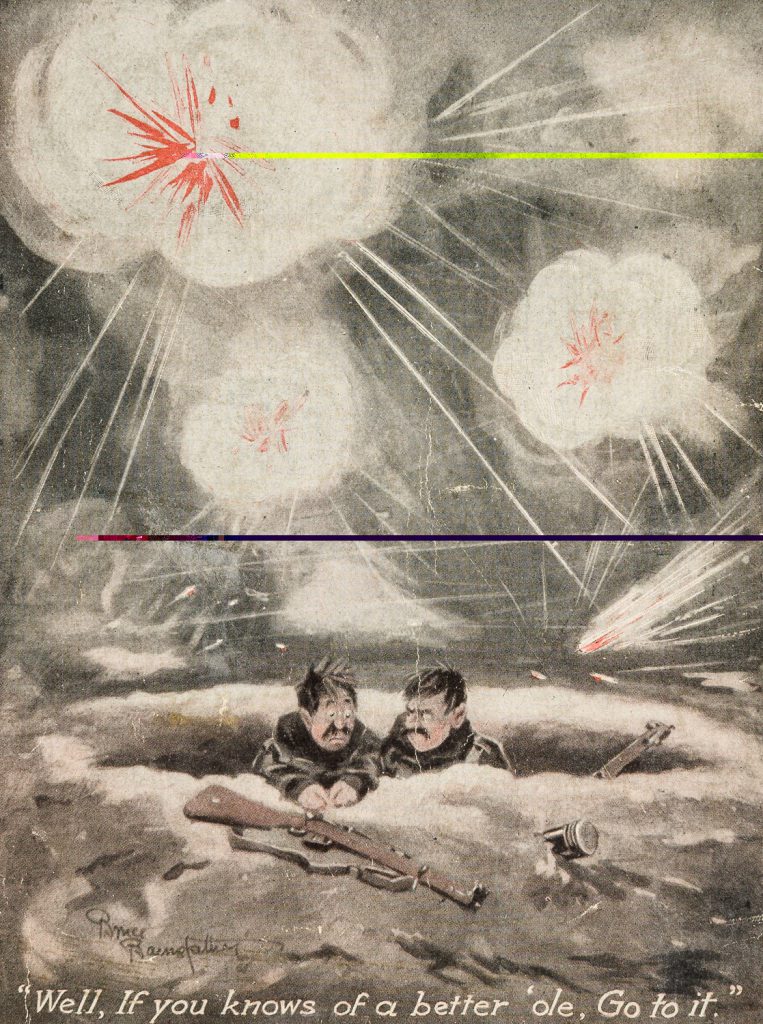

At last the time came, and we entrained for Southampton. On arrival at the docks we were to immediately board a ferry for Cherbourg. As we (the civilian four) reached the gangway, a loud voice shouted, “Stop – where do you think you are going?” It was an Officer of the Military Police. After a short conversation with our sergeant it was made clear that we couldn’t go to France unless in uniform. Our eyes lit up – we had been saved at the last moment. Not so – we were then taken to a shed on the docks which was filled with pieces of British Army uniforms of all descriptions, some of it dating back to World War I. We were told to select anything which fitted, and in no time at all we were ‘properly dressed’. So I went to France in a tunic with brass buttons, puttees and a cavalry coat, all topped off with a cheesecutter hat. I was the reincarnation of Old Bill.

*2/- was how two shillings was written. It is now officially the equivalent of 10p but in 1940 it was worth about £7.00 in modern money. Still not much.