Towards evening the Yorkshireman and I came to a small town occupied, in some strength, by an American armoured unit. They fed us and told us that they had an ammunition truck going as far as Hameln on the river Weser the following morning. We were determined to sleep in a bed for the first time for over five years, so we approached one of the better looking houses in the town – which was called Baddeckenstedt – and demanded a bed for the night. We were in luck – the house was occupied by two young German women whose husbands were officers in the Waffen S.S., but who were on the Russian front. They were delighted to see us, as they were terrified of the wandering bands of released labour-camp workers roaming the area. We had a memorable night as we first went out and raided local shops for food and drink. The women begged us to take them with us the following morning, but we were ruthless in the pursuit of our own survival, and at about eight o’clock we climbed into the cab of the ammunition truck for our journey to Hameln.

The driver was a very large black man from Chicago and he took a delight in stopping in villages and getting out of his cab. Immediately, the civilians, and particularly the women, ran for their lives. Such had been the power of Goebbels’ propaganda that the population expected no mercy from the invaders.

Hameln was burning and destroyed. The bridges over the Weser were down, and the only way across was by a pontoon built by American engineers. We crossed and came to the ammunition dump. It was now late in the day so we sought and obtained permission to spend the night in a small hut which acted as a guardroom. In spite of the cognac and cigarettes it was an uncomfortable night with frequent but mainly distant explosions and the constant drone of aircraft overhead.

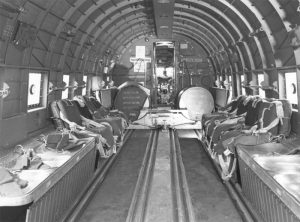

We were away early next morning, and after several miles on foot we managed to hitch a lift in a jeep driven by an American Sergeant. He eventually dropped us near to a village which he said was occupied by the British. We were cautious of contacting our own countrymen, somehow having the belief that we would be immediately drawn back into the war as fighting soldiers. However, it was not to be. We were taken to a makeshift Headquarters and underwent a long cross-examination by a British officer. He became convinced of our identity when the Yorkshireman eventually let go a stream of good Bradford oaths in his broadest dialect. We were quickly transferred to a special unit which was dealing with prisoners and refugees, and after some food we were driven to a small air-strip. After a performance of high comedy the wireless operator on the airfield managed to talk down a Dakota which was returning from a supply run.

We ran to the plane and climbed aboard. “Where are you going?” we asked the pilot. “Brussels,” he replied, in a strong Australian accent. We landed safely in Brussels about an hour later, and were taken to a small hotel for the night. Sleep was impossible, and we were not allowed out. We carefully stole soap, towels and blankets, and hoarded food as had been our habit of many years.