The Sergeant called me to his small office. He threw a piece of paper on to his table – it was a copy of an order from Hitler himself,a ‘Führerbefehl’ or Leader’s Command, which said that at a given signal all prisoners were to be eliminated. “We will not do it,” the Sergeant said, “because we have lost the war, and in any case we are soldiers of the Wehrmacht”. “You will tell your comrades,” he went on, “to get ready to move now, as I have had a further order to evacuate this camp and join up with other Arbeit Kommandos and make towards the east.” He finished cynically, “We are going to make our last stand and you will be with us.”

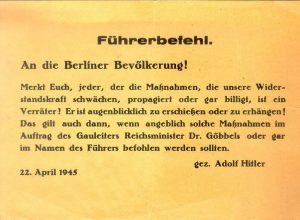

I can’t find any reference to a ‘Führerbefehl’ ordering the elimination of prisoners but it’s perfectly plausible. The ‘Führerbefehl’ above, probably Hitler’s last, is addressed to the inhabitants of Berlin in April 1945. It says that anyone weakening the resistance (to the invading Russians) is a traitor and will be summarily shot or hanged. This will happen even if the orders (to weaken) appear to come from Göbbels or Hitler.

I can’t find any reference to a ‘Führerbefehl’ ordering the elimination of prisoners but it’s perfectly plausible. The ‘Führerbefehl’ above, probably Hitler’s last, is addressed to the inhabitants of Berlin in April 1945. It says that anyone weakening the resistance (to the invading Russians) is a traitor and will be summarily shot or hanged. This will happen even if the orders (to weaken) appear to come from Göbbels or Hitler.

Our first thought was to overcome the sentries and take our chance, but we had survived too long to throw it all away in one desperate effort. Because some of us would die in the struggle, we decided to start on this journey and wait for a better moment to make the final escape. Survival was out only thought – it was truly ‘every man for himself’.

We gathered together those things which we had learned, over the years, we would need most – all the clothing and food we possessed, water-bottle, drinking cup, spoon and dish. We walked slowly for some fifteen miles, resting for five minutes in each hour, and as darkness fell we were pushed into the garage of a house in the suburbs of a small town. It was an uncomfortable crowded night on the cold concrete floor. The temperature fell to freezing in the early hours of the morning, and few of us slept. Our escorts had no food to give us so we breakfasted on our hoarded scraps, and at first light we restarted our journey. We were told that our target for the day was to be about thirty miles. By midday we had joined up with three other groups and were about a hundred strong. Significantly there was now an S.S. Officer in charge, and we saw, with dismay, the lightning flashes on the collars of the new sentries who had joined us. They used small open vehicles at the front and rear of the column, and as they changed shifts they took their turns to man the machine-guns mounted on the driving cabs.

That night we were herded into a field and spent most of the hours of darkness trying to keep warm and repairing the damage to our feet, as we were now convinced that anyone who dropped out would immediately be shot. There was still no food, but we were allowed to refill our water-bottles from a village pond.

I had made up my mind that escape from the column was a matter of urgency, and I persuaded one of my own Kommando to go with me. He was a resourceful Yorkshireman from Bradford, captured at Dunkirk, but with a record of two previous escapes, during one of which he had managed to reach occupied France and remain free for four months. We walked together the next day – we passed through small towns and villages but met with no pity from the population, who simply looked at us witn idle curiosity before going about their business. There was much damage from air attack, and four times we took cover in roadsice ditches as targets both in front and behind us were bombed and strafed.

At nightfall we had arrived at a small deserted factory and we were pushed inside to seek what comfort we could. I had noted that just outside the factory was a group of houses, each with a long garden and many having the usual garden huts. I determined this would be my last night with the column. Just after dark the Yorkshireman and I climbed to the top of the factory wall. There was no sentry in sight so we dropped quietly to the other side and ran to the nearest garden “hut”. It was a henhouse and the birds nade a fearful noise. We lay in a dark corner thinking that we would be recaptured immediately, but no-one came and, to our relief, we heard the sounds of the column moving away. We waited for about two hours, and as we whispered our plans to each other the henhouse door suddenly opened and there stood a small boy, about ten years old, with a basket in his hand. He had come to collect the eggs. He took one look at us – we presented a fearful spectacle – filthy, bearded, covered with bird droppings and gaunt with hunger and fatigue. He dropped his basket and ran screaming to the house. Before we could move, his father – a Corporal in the German Volksturm (or Home Guard) had arrived with a Luger pistol in his hand. He was an old man, and plainly very frightened, but in no time neighbours had gathered, armed with shotguns, pitchforks and axes. We had no alternative but to surrender. We were rushed back to the column at a half-run, and taken to the S.S. Officer. He screamed at us and drew his pistol. I felt that all my careful efforts to survive had now come to nothing, and I was to die on this cold, miserable road in some remote part of North Germany. I closed my eyes, and then suddenly realised that the officer was ordering the sentries to ensure that the Yorkshireman and myself marched in the front row of the column from now on.

We were in a desperate position, as we had lost all our possessions and would have to rely on the charity of others. This would not be easily forthcoming, as personal survival was every man’s total pre-occupation. We walked all that day, and to add to our despair it rained heavily. We judged that we were moving towards Magdeburg. What we did not know was that only about thirty miles behind us were American tank units, and that the Russians were advancing swiftly towards the Elbe about sixty miles in front. There was no sign of change in the German civilians, although we did see evidence of newly-dug slit trenches and hastily constructed defence posts outside towns and villages. We were about to be crushed between the hammer and the anvil, but there was to be a way out, and this we would find on the next day.

As the long wet fourth day of our journey came to its end we were shepherded into an empty warehouse. It had three storeys and a population of rats. The sentries took up their positions around the building and we settled down for the weary night. Although saturated, cold and hungry, I slept a sleep of sheer exhaustion.