It was now December and the weather had turned very cold. There was still no sign of the dreaded “Arbeit”, which was perhaps just as well as we were getting weaker by the day. The camp had ‘officer’ compounds and as British officers were in the next enclosure to ours we were able to exchange words with them. I remember seeing F.R. Brown and Bill Bowes, both England cricketers, throwing a ball to each other. Their situation, like their fellow officers, was more promising than ours because by international convention officers did not have to work and could spend more time on survival, and even escape. The reason there were fewer escapes by other ranks was simply that the cumulative strain of insufficient food and hard labour made planning and executing escape almost impossible.

A few days before Christmas – it was now 1943 – our ‘compound’ was ordered to gather together our belongings and march to the railway halt. We were once more put into the hated cattle trucks, which set off northwards. Now was to begin the hardest Christmas we had ever spent. After about three days’ travel – we had been given water and hard rations – we came to a halt in a siding near Saltzgitter in western Germany. The guards refused to answer any questions, and ignored our requests to be given water and let out for exercise. It was now Christmas Eve, and we settled down the straw for the miserable and bitterly cold night. Suddenly in the darkness, the clear tenor of Frank Kennard began “Silent Night”. Within a few moments we were all singing, and our look-outs at the grills reported that the sentries were joining in. Our carols had no effect on our situation but they did offer us some comfort. It was not until noon the next day – Christmas Day- that the doors were eventually unbolted and we scrambled out to be formed up and marched about half-a-mile to a prison camp. None of us knew anything about concentration or extermination camps or we might not have felt so relieved to be out of the train. However, we were not to be harmed. We were given a meal of soup and black bread, and on this occasion there was as much as any of us could eat. Being wily P.O.Ws. by now, we saved as much bread as we could for later use. We were not to stay in Saltzgitter, and after our meal we went back to our cattle trucks and were once more locked in. After some hours the train started, and we continued our journey north. Our only consolation was that we felt that we were getting nearer to our own country all the time.

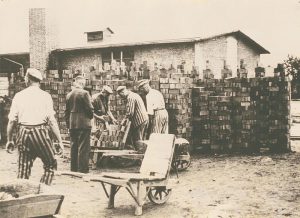

Again, after what seemed to be an eternity, we halted and the doors opened with the usual shouts of “raus”, and indiscrimate blows from rifle butts, to ensure that we got out quickly. This time the camp was quite new. We were at Fallingbostel, which once more was only a staging post for further dispersal. This camp was a different type from the one at Moosberg. We slept in bunks three tiers high, and for the first time we saw in neighbouring compounds men in a type of striped pyjama suit who appeared to be undergoing a very tough regime. We were told that they were political prisoners and black marketeers. We did not realise that we had seen our first concentration camp.

Concentration camp inmates working at the brickworks in the camp next to Dad’s POW camp at Fallingbostel

I was to have a stroke of luck after a few days. Frank Kennard, an accomplished pianist as well as a singer, was ordered to the German Officers’ Mess where he was told to sing and play whilst the officers had their meals. His first instinct was to refuse this order, but he realised that he could learn much about the camp and its surroundings, so he accepted. He asked if he could take me with him as a ‘page-turner’ for his music, and a general assistant. The Germans agreed, and so began a short but interesting interlude. We were also quite well fed as we got the left-overs from the Officers’ tables. This episode came quickly to an end as far as I was concerned. We had to parade each day in our huts at 7 a.m. with whatever meagre kit we had, laid out for inspection. One morning my ‘layout’ was not considered satisfactory by the inspecting officer and I was given 48 hours in the ‘cooler’. This was a prison within a prison and consisted of life in a tiny cell. Part of the ‘treatment’ was to experience alternate periods of heat and cold by use of the piped water system which flowed through the cell. Just as you had cast off most of your clothes to adjust to the hot period, the cell quite quickly became icy cold. I would not have liked to have gone more than 48 hours under this regime, but I was able to relieve the monotony by tapping out morse messages to the prisoner next door who was a Frenchman. After the due time had elapsed I was allowed back into the main camp, but I had lost my job as Frank Kennard’s assistant, and I was assigned to the woodcutting party in the local forests. The work was not too arduous as long as we completed our quota each day. It was nothing to what we would experience later when we were parcelled out in small groups to Arbeit Kommandos, or work units.