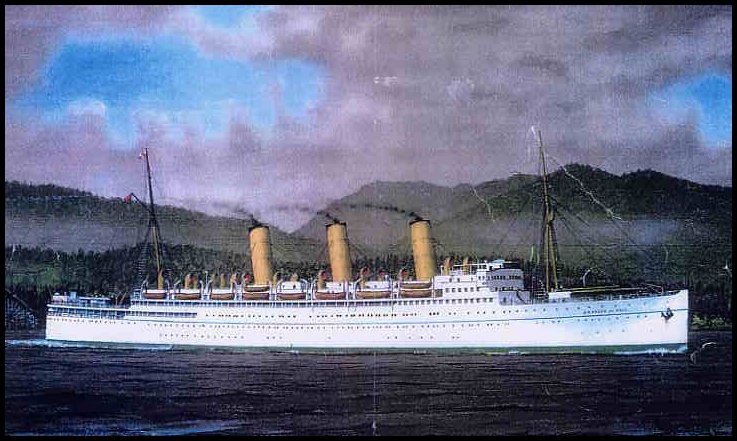

The war was now raging in Egypt and Libya, and the 50th Division was ordered to the Middle East to reinforce the 8th Army. We boarded the Empress of Asia at Liverpool and sailed up to Glasgow where a convoy was formed in the Clyde. Conditions on board were appalling. We were crowded together and slept in hammocks three decks down, but we had no idea of what was yet to come. We did the usual boat drills and had P.T. on the decks together with weapon training and interminable lectures. We members of the Royal Corps of Signals had to take a ‘watch’ on the bridge and assist with the signalling between ships. This was just a joke at first because the Navy operators, who were used to lamp signalling, found our efforts very poor, and made many requests for ‘repeats’

We set off into the Atlantic escorted by an aircraft carrier, two cruisers and many destroyers. We did not realise it but we were one of the most valuable convoys to leave Britain, carrying a whole Division with support troops and artillery etc. We had been sailing about four days when the weather changed and many men became very seasick, and conditions below decks deteriorated even further. The food was practically inedible, and when a man who was acting as a waiter in the Officers’ dining room brought us a menu card showing the difference in the quality of food as between officers and men we began to feel quite mutinous. One young officer who came to inspect us was invited to taste our ‘lunch’. He bravely did, then was promptly sick!

-

Empress of Asia -

Bismarck

We awoke one morning to hear an announcement which went something like this – “The Battleship Bismarck has left her berth in Norway and is heading in to the Atlantic in the general direction of this convoy. We have been ordered to scatter.” Within no time our escort vessels had disappeared, and a few hours later we were alone. We were now very vulnerable but, fortunately, we were not attacked and after a few days put in to Freetown in Sierra Leone. We anchored about a mile off shore and stayed for two days taking on supplies and water. We entertained ourselves by throwing coins for native divers on the “bum boats” which came out to try to sell us all sorts of trinkets and fruit. It was extremely hot, and we were allowed to sleep on deck if we could find a shady spot. Many of the officers went ashore by launch, and we really envied them their luck in being able to walk on dry land.

After a few days we sailed unescorted down the African coast and eventually put in to Capetown. It was a memorable sight – not only to see Table Mountain but to watch all the lights go on in a city the war had not yet touched. We had been briefed as to our behaviour in Capetown because it was the intention that shore leave would be granted to as many as possible. The briefing was interesting in the light of modern events. We were told that on no account were we to speak to any black person, and above all to keep out of District 6, which was largely an area where non-whites lived. It was pointed out to us that blacks had separate compartments on public transport and even separate seats on public benches. There was much leg-pulling of the one black soldier we had in our unit, and we all decided to ignore these ridiculous instructions.

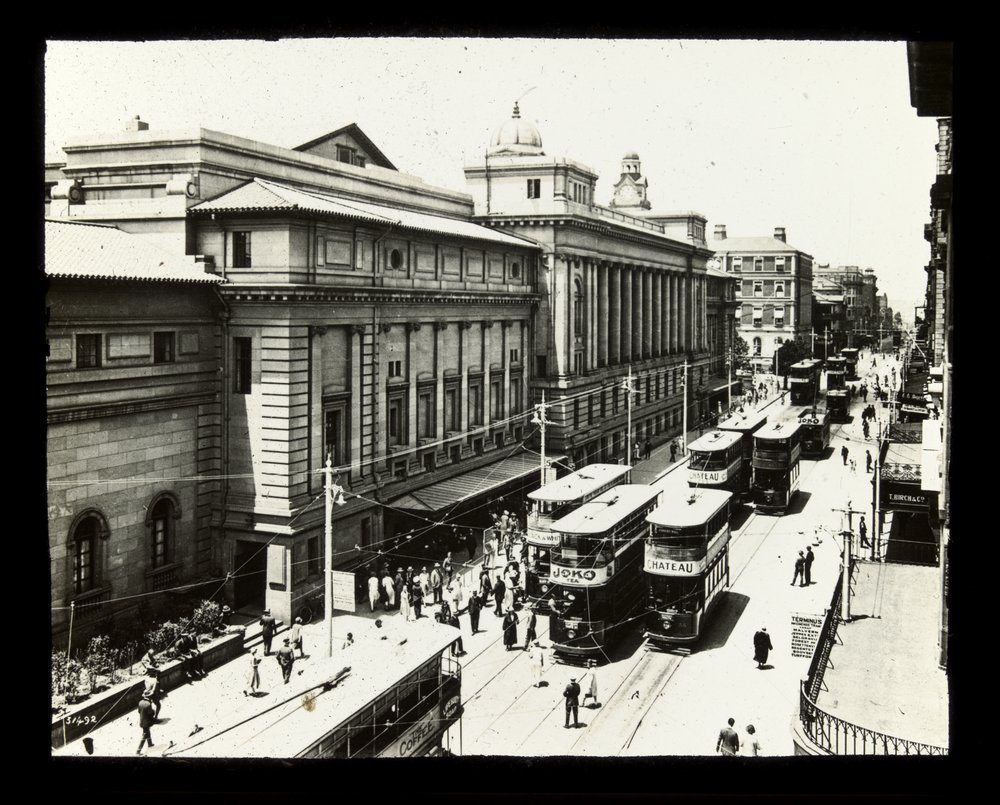

-

Adderley Street about 1930 -

Table Mountain

It came my turn for “shore leave’. I had been promoted to Lance-Corporal, but this was to prove to be a considerable disadvantage. We were warmly welcomed by the people of Cape Town, and I met a very charming Dutch girl who invited me to her home and corresponded with me and sent me parcels for the next few months whilst I was in the Egytian and Libyan deserts. However, this pleasant interlude was not to last. On the second day, as I was walking down Adderley Street with two others trying to find a restaurant where we could have a good meal, a voice from the other side of the street bellowed “Corporal!” Not realising that it meant me, I ignored it, whereupon a very large sergeant of the Military Police crossed the road and confronted me. “Are you deaf. Corporal?” he shouted. “No, Sergeant”, I replied politely. He then produced a wretched half-drunken private of the Durham Light Infantry and said, “Escort this man back to the ship, and see that he is put in to the brig. He’s probably going to be court-martialled.” My protests about losing my “leave” were in vain. The inebriated private and I set off in a taxi for the “Empress of Asia”. I had to pay the fare, and I was never able to recover this. Apparently the ‘prisoner’ had not only had too much to drink, but had succeeded in breaking a shop window and damaging the contents. I had now become, through no fault of my own, inextrically embroiled with the case, and I was confined to the ship whilst a summary board of enquiry was conducted. My job was to give evidence of arrest, and as the enquiry continued until the ship sailed, my ‘leave’ had been brief indeed. The Durham Light Infantry man was sentenced to twenty-eight days’ detention, which he served on ship. He later told me that it wasn’t too bad because the food was better in the brig, and he had a cell to himself.